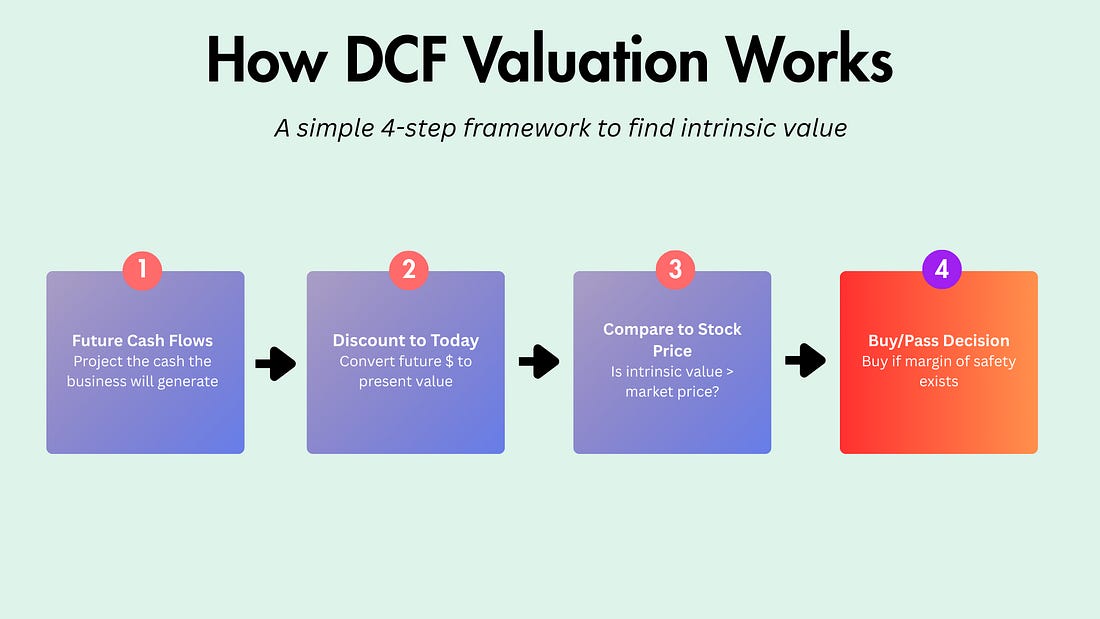

Everyone talks about “intrinsic value,” but how do you actually calculate it? Here’s the truth: most investors never move beyond looking at price-to-earnings ratios and hoping a stock goes up. They’re essentially flying blind, hoping the market agrees with them someday. But professional investors take a different approach: they calculate a business’s actual value, independent of market sentiment. That’s where Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) valuation comes in. It’s how Warren Buffett(in theory), quality-focused fund managers, and serious long-term investors determine what they should pay for a piece of a business. And while it might sound intimidating, I’m going to break down DCF step-by-step with visuals that make it click. What is DCF? (The Big Picture)DCF stands for Discounted Cash Flow. The core idea is elegantly simple: a company is worth all the cash it will generate for its owners in the future, adjusted to today’s dollars. Think of it like this: if you were buying a rental property, you wouldn’t just look at the asking price. You’d calculate how much rent you could collect over the years, factor in expenses, and decide what that future income stream is worth to you today. That’s exactly what DCF does for stocks. Here’s why this matters: DCF separates price (what you pay) from value (what you get). The stock market tells you the price every second of every trading day. But only fundamental analysis can tell you the value. When you find a situation where value exceeds price by a comfortable margin, you’ve potentially found a good investment. The math might look complex at first, but the concept is intuitive: a dollar today is worth more than a dollar five years from now because you could invest that dollar today and earn a return. DCF accounts for this time value of money. The 5 Components of DCFEvery DCF model has five key inputs. Master these, and you’ve mastered the framework. Component 1: Free Cash Flow (FCF)Free Cash Flow is the lifeblood of any DCF model. It’s the cash a business generates after paying all its expenses and reinvesting what’s needed to maintain and grow the business. You find FCF on the cash flow statement. The formula is simple: Free Cash Flow = Operating Cash Flow - Capital Expenditures. Why does FCF matter more than net income? Because cash is real. Accounting profits can be manipulated with depreciation assumptions, revenue recognition choices, and other estimates. But cash is cash; it’s what the business can actually use to pay dividends, buy back shares, pay down debt, or reinvest for growth. Let me show you what this looks like with real numbers. According to Microsoft’s fiscal year 2024 10-K filing (year ended June 30, 2024):

Source: Yahoo Finance SEC data from Microsoft’s cash flow statement, fiscal year 2024 Component 2: Growth RateThis is where you project how fast FCF will grow over your forecast period (usually 5-10 years). You’re making an educated guess based on:

Here’s the reality check: most companies can’t grow 20%+ forever. Even the best businesses eventually face the law of large numbers. Microsoft’s FCF has grown at varying rates from:

That’s about 3% annual growth over that period, though individual years vary. For a mature, high-quality business like Microsoft, a reasonable long-term FCF growth assumption might be 8-12% over the next 5 years, then slow thereafter. Component 3: Terminal ValueTerminal value represents all the cash flows beyond your projection period. If you project 5 years out, the terminal value captures year 6 through infinity. This matters because terminal value often represents 60-80% of your total DCF value. Small changes in your terminal value assumptions create big swings in your final answer. There are two methods: Perpetual Growth Method: Assumes the company grows at a modest rate forever (usually 2-3%, roughly GDP growth) Exit Multiple Method: Assumes you could sell the business at a certain multiple of FCF or EBITDA in year 5 Most investors use the perpetual growth method for stable businesses. The formula: Terminal Value = Year 5 FCF × (1 + perpetual growth rate) / (discount rate - perpetual growth rate) Component 4: Discount Rate (WACC)The discount rate is your required return—what you demand to compensate you for risk and the time value of money. For most public companies, investors use WACC (Weighted Average Cost of Capital), which is typically 8-12% for stable businesses. Higher-risk companies warrant higher discount rates. Why do we discount? Because $100 today is worth more than $100 in five years. You could invest $100 today at 10% and have $161 in five years. So $100 in five years is only worth $62 today at a 10% discount rate. Simple rule: higher risk = higher discount rate = lower valuation. This builds in your margin of safety. Component 5: Present ValueThis is where we bring all those future cash flows back to today. The math: Present Value = Future Value ÷ (1 + discount rate)^number of years For example, if Microsoft generates $85 billion in FCF next year and our discount rate is 10%: PV = $85B / (1.10)^1 = $77.3B You do this calculation for every year of projected FCF, add up all the present values (including the terminal value), and you get the total enterprise value. Subtract net debt, divide by shares outstanding, and you have intrinsic value per share. A Simple DCF Example: MicrosoftYou've got the framework. Now let's put it to work. In the next section, I'll walk you through a complete DCF valuation of Microsoft—step-by-step, with real numbers pulled from their 10-K filing. You'll see how each component we just covered turns into an actual intrinsic value estimate... Continue reading this post for free in the Substack app |

0 💬:

Post a Comment